INTRODUCTION

During the difficult years of World War II, a group of Spanish diplomats and members of Spain’s Foreign Service posted in Holocaust Europe were able — through humanitarian response and respect for human dignity — to save thousands of Jews from deportation and extermination. Without their selfless protection, these Jews would have inevitably met their deaths.

The individual actions of these Spanish officials went above and beyond mere compliance with their ethical or professional duty: guided by conscience alone, not consulting with their government, and at times even openly going against its policies, they risked their careers, their own lives, and even their families’ safety in order to defend fellow human beings (in most cases, other Spaniards), regardless of race or religion.

In the face of ethnic persecution — whether legal or physical — many Jews found in Spain’s diplomatic missions the solidarity and assistance of civil servants of the Foreign Service, committed to ethics and morals, to honesty and integrity, even in cases where higher State interests could have been compromised.

Defying Nazi brutality, they interpreted “generously” the instructions received from Madrid and, at their own initiative, issued documents of protection, released detainees, provided hiding places, enabled escape, organized repatriation... For them, the purpose of their duty as public servants was no less than safeguarding freedom and guaranteeing life.

Most of them kept their actions secret; they never talked about the good that they did. Their silence — even with their own families, who would only learn what really happened many years later — was inherent to their mission. Therefore, their names and deeds have been unjustly relegated to anonymity for decades, and their commitment and ingenuity have gone unacknowledged. Consuls general, ministers, chancellors, vice-consuls, chargés d’affaires and attachés all worked with admirable humility and absolute discretion to protect Spanish Sephardim under General Primo de Rivera’s 1924 Decree.

Their motivations were varied: for some, protecting their fellow nationals was a legal principle or even a question of patriotic pride; others were moved by profound beliefs and principles, whether Christian or simply humanistic; many felt sympathy towards the Sephardic world, which they had come to know in previous diplomatic posts; all of them were moved by undoubtedly praiseworthy values.

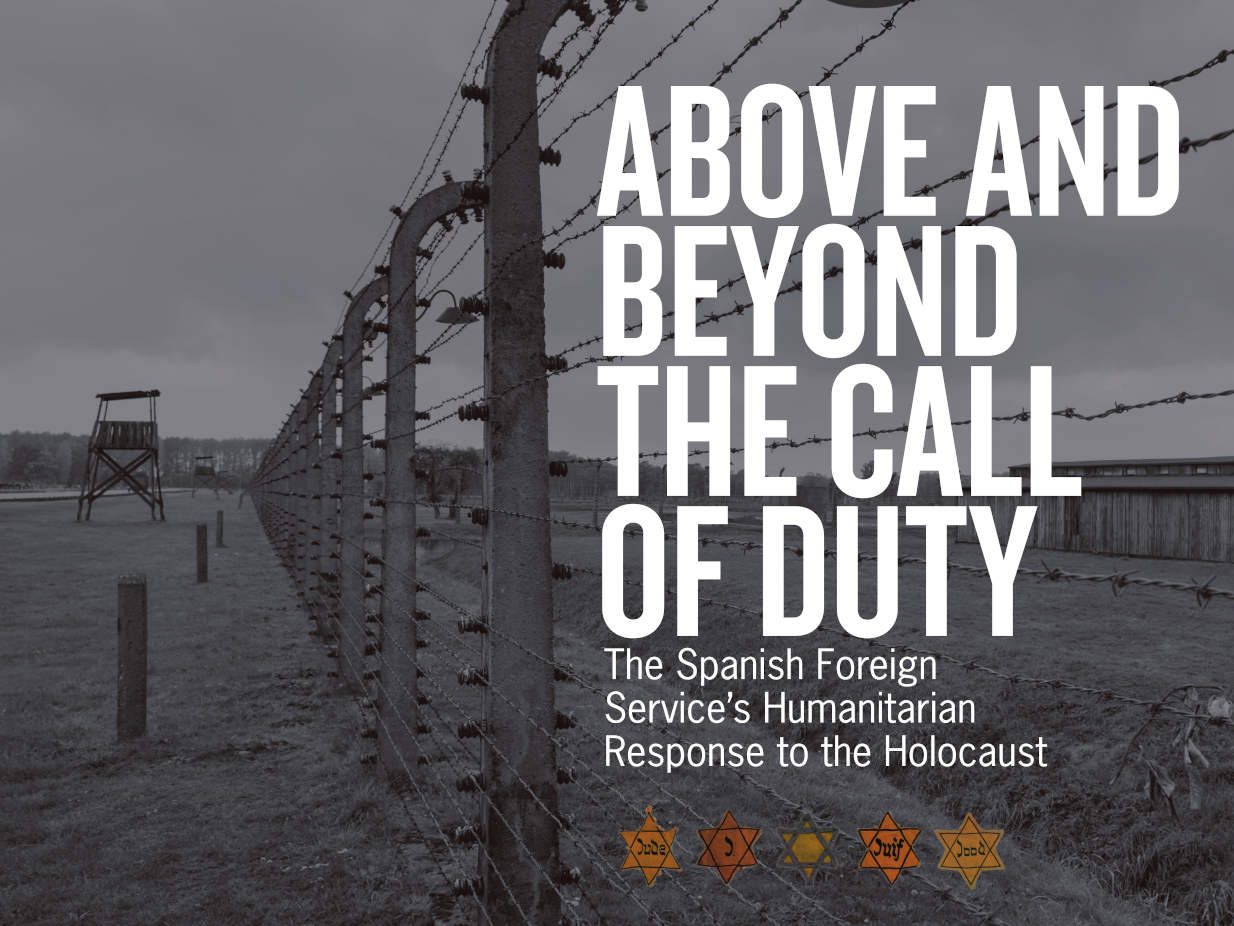

The debt of gratitude that we owe them makes the exhibition “Above and Beyond the Call of Duty” a just tribute to the courage and tireless efforts of those diplomats and civil servants in Spain’s Foreign Service who saved thousands of lives, regardless of borders or labels of race, nationality or religion. Keeping their memory alive ensures that they will be remembered and constitutes an unquestionably well-deserved tribute.

José Antonio Lisbona CURATOR

Loading

Loading