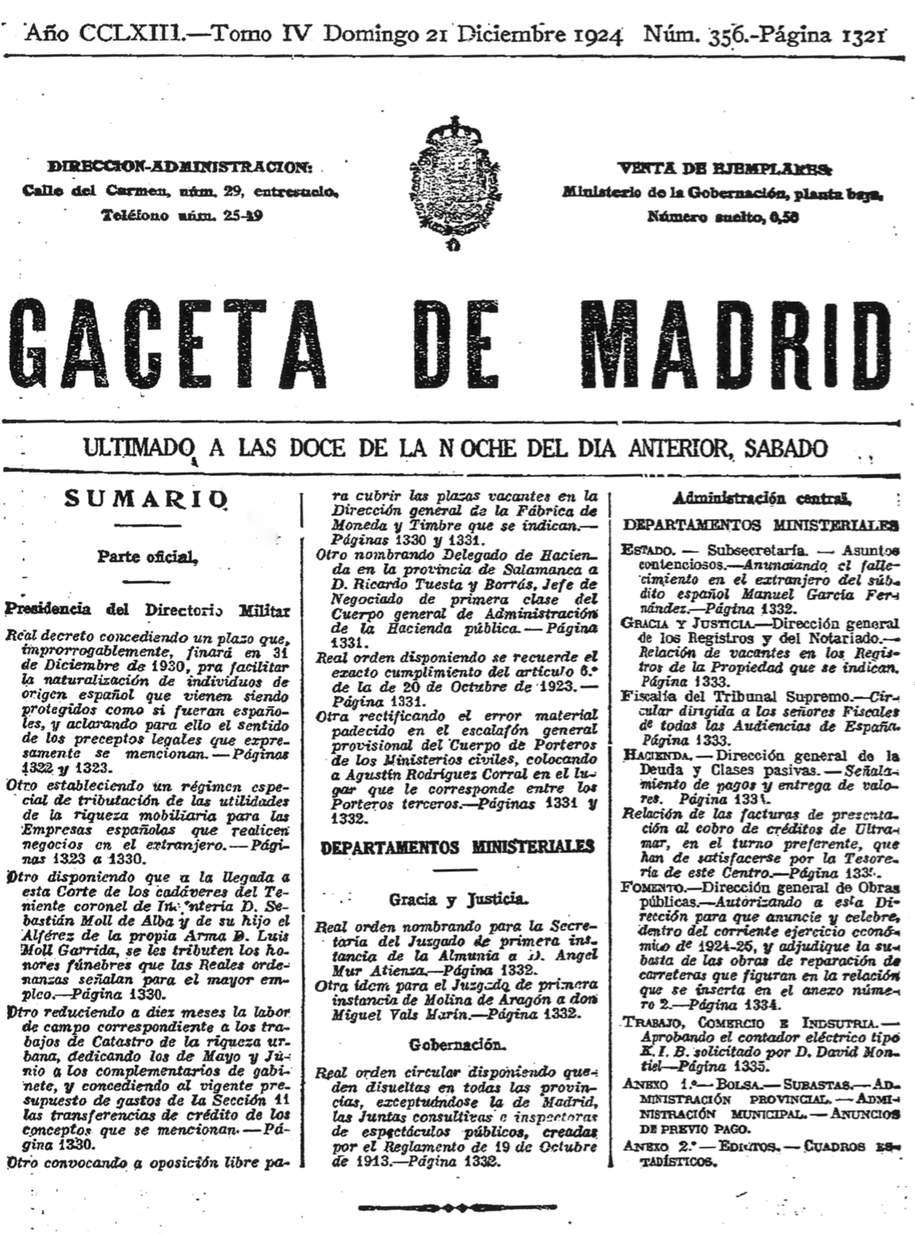

PHILO-SEPHARDISM AND THE 1924 ROYAL DECREE

"Spaniards without a homeland"

From the beginning of the 20th century, public opinion in Spain began evolving towards positions of clear sympathy regarding the Jewish question, especially towards the Sephardim, Jews of Spanish descent.

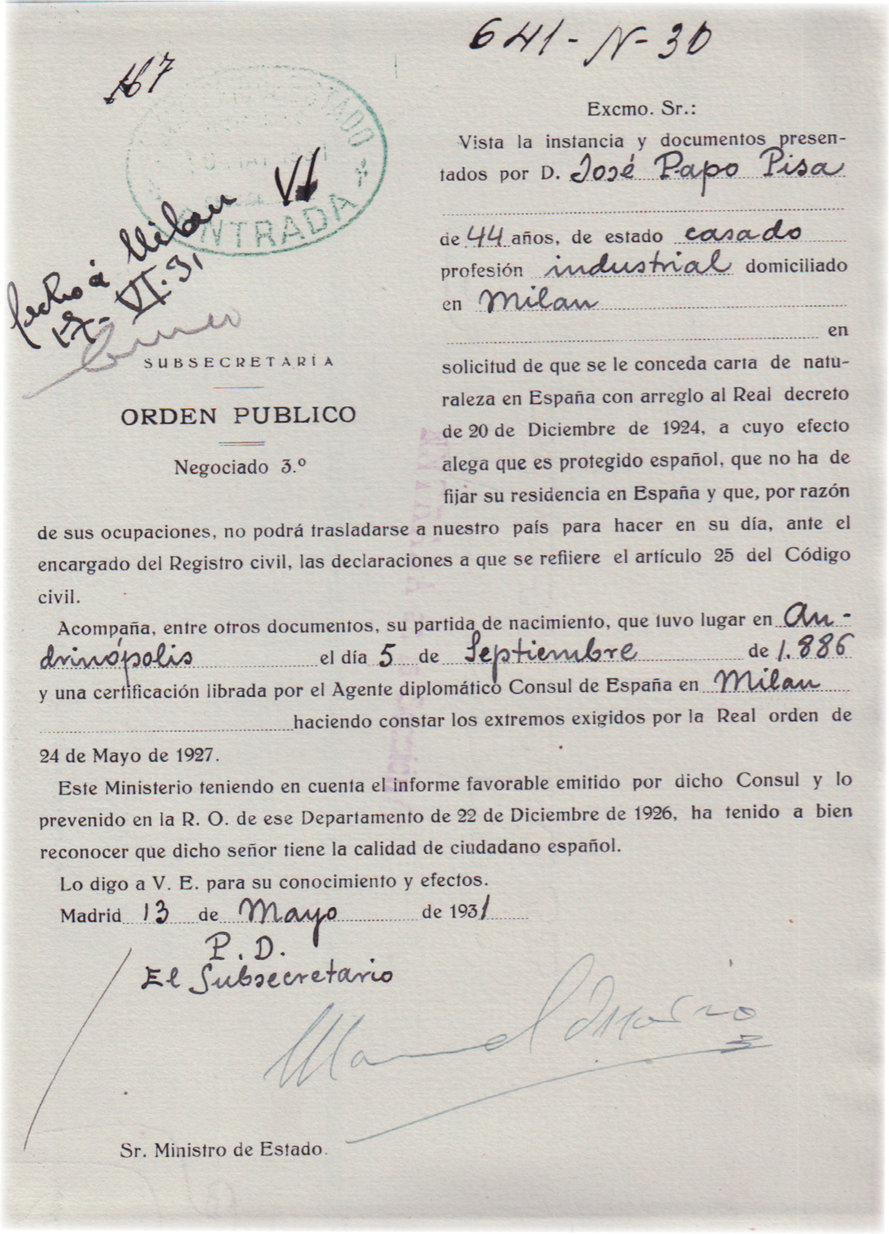

Document granting nationality through naturalization to José Papo Pisa, a Sephardi from Milan, by the Under-Secretary of the Ministry of State, pursuant to the Royal Decree of 20 December 1924.

Passports issued in 1938 and 1934 by the Consulate of Spain in Budapest to two Sephardim residents in Hungary.

This "discovery" led to a spirited philo-Sephardic campaign, soon reaching the realms of culture and politics. Figures such as the Count of Romanones, Pérez Galdós, Canalejas, Maura, Ramón y Cajal, Menéndez Pidal, Alcalá-Zamora, De la Cierva, Lerroux, Azcárate and Azaña openly favoured the Sephardic cause. But it was not only intellectuals and politicians of that time who were philo-Semi - tic; King Alfonso XIII himself took action to protect Jews. Years before, in 1881, Prime Minister Sagas-ta's Government — in the name of King Alfonso XII — had offered Spanish territory as a haven for thousands of Russian Jews, victims of the bloody Tsarist pogroms, who asked for help.

A true champion of philo -Sephardism, as an endea-vour of national interest, was Senator Ángel Pulido. His campaigns in favour of "Spaniards without a homeland" earned him the sobriquet "apostle of the Sephardic cause".

The survival of the Judeo-Spanish language, spoken by the Sephardim more than four centuries after their expulsion from Spain, was also greatly admired among intellectuals. A group of writers — the leading literary figures of the time — were interested in Sephardic issues: Unamuno, Menéndez Pidal, Pardo Bazán, Valera, Pérez Galdós, Bretón, Camba and Echegaray, to name a few.

However, the Spanish government's rapprochement would merely be part of a symbolic and sentimental movement, until the debate arose regarding whether Spain would unilaterally grant naturalization to protected Sephardim, through a privileged legal procedure.

After World War I, the Treaty of Lausanne of 24 July 1923 formalized the end of the Ottoman capitulations system, one of the expressions of which conceded the right of protection by foreign powers to certain residents in Turkey. With the disappearance of the Ottoman Empire, other burgeoning states in the Balkans and in the Arab world decided to adopt the same measure.

The ensuing situation placed the Sephardic communities of the Middle East in a desperate position, without rights or protection, in countries that were implementing severe nationalist policies. Traditionally, Spain had extended its protection to those "quasi-naturalized" Sephardim, but given the circumstances, their situation could not last indefinitely and a legal solution was necessary to provide them with a homeland. To this end, the Military Directory of General Primo de Rivera enacted the Royal Decree of 20 December 1924, whereby Spanish citizenship was granted to "former Spanish protectees or their descendants, and in general individuals belonging to families of Spanish origin who at any time have been listed on Spanish Registers".

This Royal Decree undoubtedly gave all these protectees an opportunity to legalize their nationality. However, the Royal Decree was barely publicized and was less successful than expected: a mere 4000 people responded to the offer. Many Sephardim believed it was sufficient to have a Spanish passport, even though they were not listed in the Civil Register or in consular registers and, accordingly, considered it unnecessary to take advantage of the Royal Decree.

Neither the Royal Decree nor Circulars and Royal Orders issued subsequently make any reference to Jews or to Sephardim; they do not even mention them. However, the Directory believed that the vast majority of beneficiaries would be "the lost children of Spain".

The Royal Decree has often been solely considered the result of Senator Pulido's campaign. Nevertheless, it had an extraordinary, much further reaching significance: it created the legal basis for granting consular protection during World War II to those Sephardim who had obtained Spanish nationality under the decree. Moreover, it was the instrument cleverly used by Spanish diplomats to offer a humanitarian response to Nazi barbarity and thus save the lives of thousands of Jews during the Holocaust.

The Germans did not question the validity of these Jews' nationality; in fact, they did not make any objection to the legal status of the Spanish Jews "saved" by the 1924 Royal Decree, the decree on freedom.

Loading

Loading

![Cover of Españoles sin Patria [Spaniards without a Homeland], a book by Senator Pulido, the champion of philo-Sephardism.](img/PANEL_3_ph_7_cut.jpg)