AGRICULTURAL ATTACHÉ

(BERLIN 1942-1944)

JOSÉ RUIZ SANTAELLA AND CARMEN SCHRADER

Hiding in the shadows

José Ruiz Santaella (1904-1997), whose parents were labourers from Baena, Cordoba, was the nineteenth of twenty-one children. He studied agricultural engineering in Madrid, and three years after graduating in 1931, earned his doctorate from Halle-Wittenberg University, in Germany. There, he met Waltraud Schrader Angelstein (1913-2013), born to a Protestant family in Saxony. They were married in 1936, and she converted to Catholicism and took Spanish citizenship, changing her name to Carmen. He was 30 years old at the time, and she was 21. As the racist Nuremberg Laws were in force, in order to marry, José had to present a baptismal certificate from his parish in Baena, showing that he had no Jewish blood. This was his first personal contact with the anti-Semitic reality of Nazi Germany.

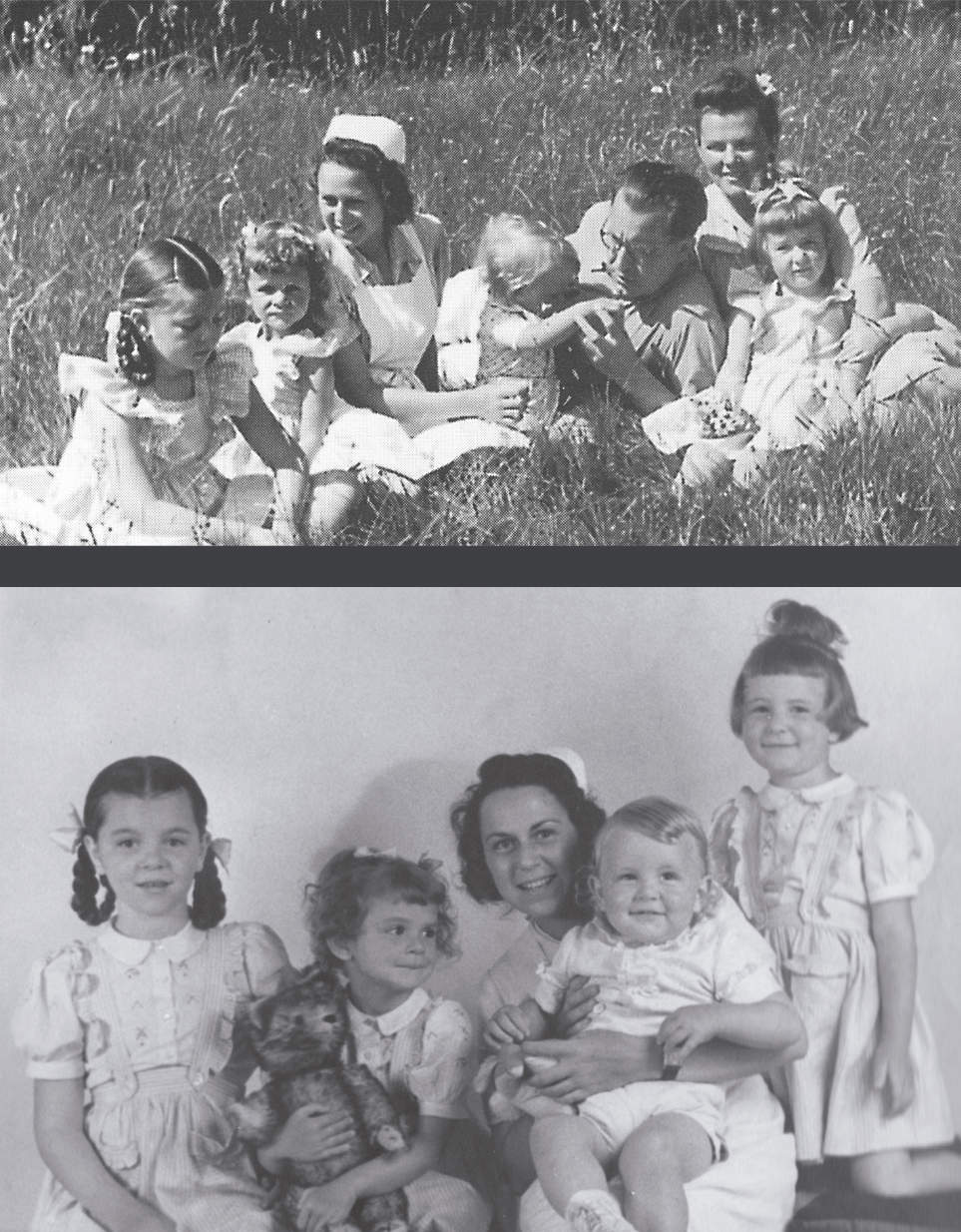

Since Santaella had studied in the country, spoke the language perfectly and had German in-laws, this paved the way for him to take a position, in December 1942, as the new Agricultural Attaché at the Spanish Embassy in Berlin, where the young couple lived for some months, later moving to Diedersdorf, 62 kilometres away. By then they had four children, and so preferred to live in a bigger house in the country.

Under the privileged cover of their diplomatic status, from April to September 1944 José Ruiz Santaella and Carmen Schrader hid three Jewish women at their Diedersdorf residence, giving them fake identities as servants. By doing so, the couple was taking a huge personal as well as professional risk: had they been caught, it would have created a very serious diplomatic incident.

The first of the three, Gertrud Neumann, had miraculously survived jumping out of a moving truck as it took her to an extermination camp. From the spring of 1943, she lived underground, passing as an Aryan and working as a seamstress several days a week for the Santaella family while they were still living in Berlin. Having realized the couple's deep humanitarian convictions, the anguished woman confessed to them that she was of Jewish origin. The Santaellas hired her as a live-in servant, and urged to come with them for protection when they moved to Diedersdorf. When she learned that Carmen was seeking a nanny for her four children, Neumann dared to recommend that the hire Ruth Arndt, the daughter of her doctor, who was a very well-known Jewish psychiatrist.

The Santaellas were impressed by the Arndt family's story: they were living underground, threatened with deportation if they were found. In April 1944, they hired the young Ruth, who had experience as a paediatric nurse; shortly thereafter, they gave shelter to her mother, Lina, hiring her as a cook. As for the father of the family, Dr Arthur Arndt, he found refuge in the basement of a former patient, and Santaella personally brought him food when possible.

To avoid arousing suspicions amongst the other household staff — including a girl who was a member of the Hitler Youth — the Santaellas gave the Arndts fake identities. Ruth became the nurse Ruth Neu, moving into the bedroom where the three little Santaella sisters and the baby slept, while Lina was called Frau Lieschen Werner and shared a room with Gertrud. Mother and daughter kept their relationship a secret. In addition to this protection, the three Jewish women also received their regular salary from the Santaellas.

In the face of the Allied advance and the constant bombing of Berlin, on 15 September 1944 Santaella was sent to the nearby Spanish Legation in Berne. José and Carmen considered taking Ruth with them, hidden in the trailer being pulled by their car with its diplomatic license plates — but the plan was abandoned because of the danger of discovery. Once installed in Switzerland, they continued to take care of the Arndt family for the rest of war, sending them ration cards and packages of food via Max Kӧhler, a local hire at the Spanish Embassy. The Arndts were one of the few Jewish families in which every member managed to survive by staying in hiding until Berlin was liberated.

In 1946, the Amdts emigrated to the United States. The former nanny would live in New York and California until her death in May 2012, at the age of 90. She maintained a lifelong friendship with the Santaella family, whose daughters always called her Auntie Ruth.

On 13 October 1988, José Ruiz Santaella and Carmen Schrader were declared Righteous among the Nations by Yad Vashem.

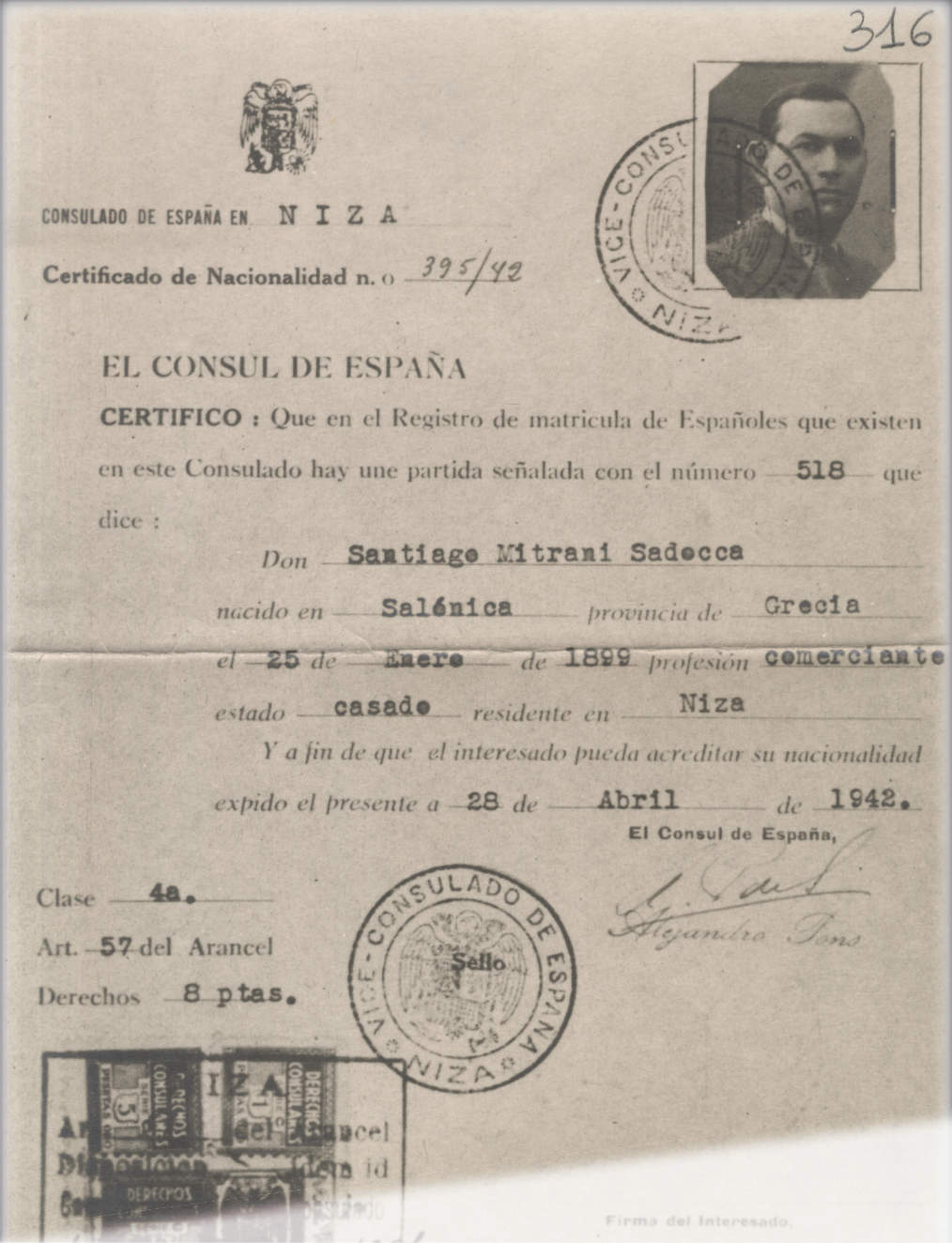

HONORARY VICE-CONSUL

(NICE, 1939-1944)

ALEJANDRO PONS BOFILL

Killed in the line of duty

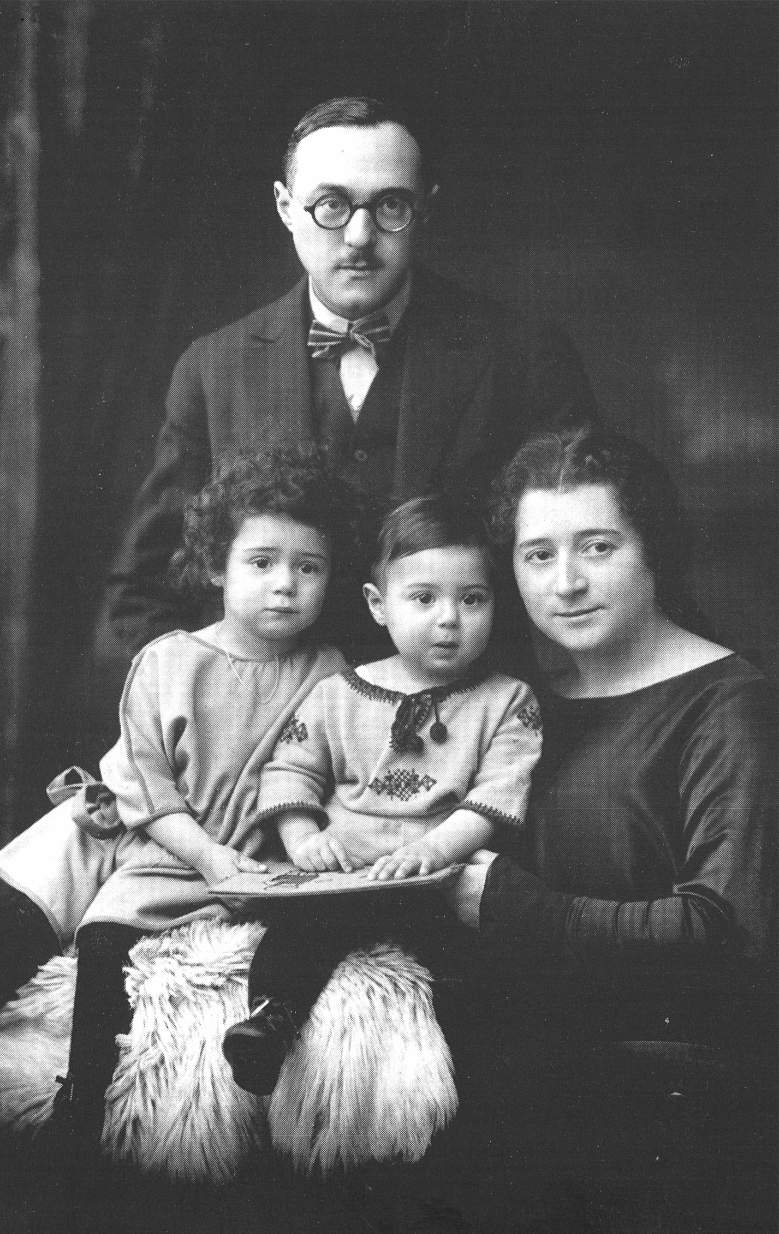

When, thanks to his relationship with monarchist circles and Cambós Lliga Regionalista party, Alejandro Pons Bofll (1896-1944) received his posting to Nice, there were about 2000 Spaniards and 15,000 Jews residing in the Alpes Maritimes department, and Nice was France's fourth-largest city, with approximately 210,000 inhabitants.

A 43-year-old native of Barcelona, married to US citizen Maribel Krippendorf, Pons came from a family of Catalan businessmen and politicians: his father, Alejandro Pons y Serra, was a member of Parliament and of the Senate under King Alfonso XIII, and his brother-in-law, Juan Teixidor, was a diplomat, Minister-Counsellor at the Holy See.

In December 1942, Pons recommended that Spanish Jews not go to the Prefecture to have their identity documents and ration cards stamped with a J for Jew. He wrote to the prefect saying that in Spain there was no distinction between races and that all Spaniards had the same rights, and he achieved a postponement for the stamping. In parallel, he issued certificates stating that, given their Spanish nationality, their holders benefited from the 1862 Consular Convention between Spain and France in force at the time. He continued giving out these certificates—unbeknownst to the Consul in Marseille, to whom he reported—until the German occupation in September 1943.

Pons repeatedly interceded before the General Commissariat for Jewish Affairs of Vichy France in defence of the assets and property of Spanish Jews; for instance, of Samuel Frances, Adolfo Gruenebaum , and Laura Hass de Saporta. He skilfully prevented hasty liquidations carried out with no guarantees and at low prices. Despite the Prefecture's reluctance, Pons managed to have Spanish administrators replace the French administrators imposed by Vichy. Faced with the plundering of people's homes, he lodged many complaints before the Nazi police commander, and decided to stamp doorswith a Special Certificate of Spaniards' Assets.

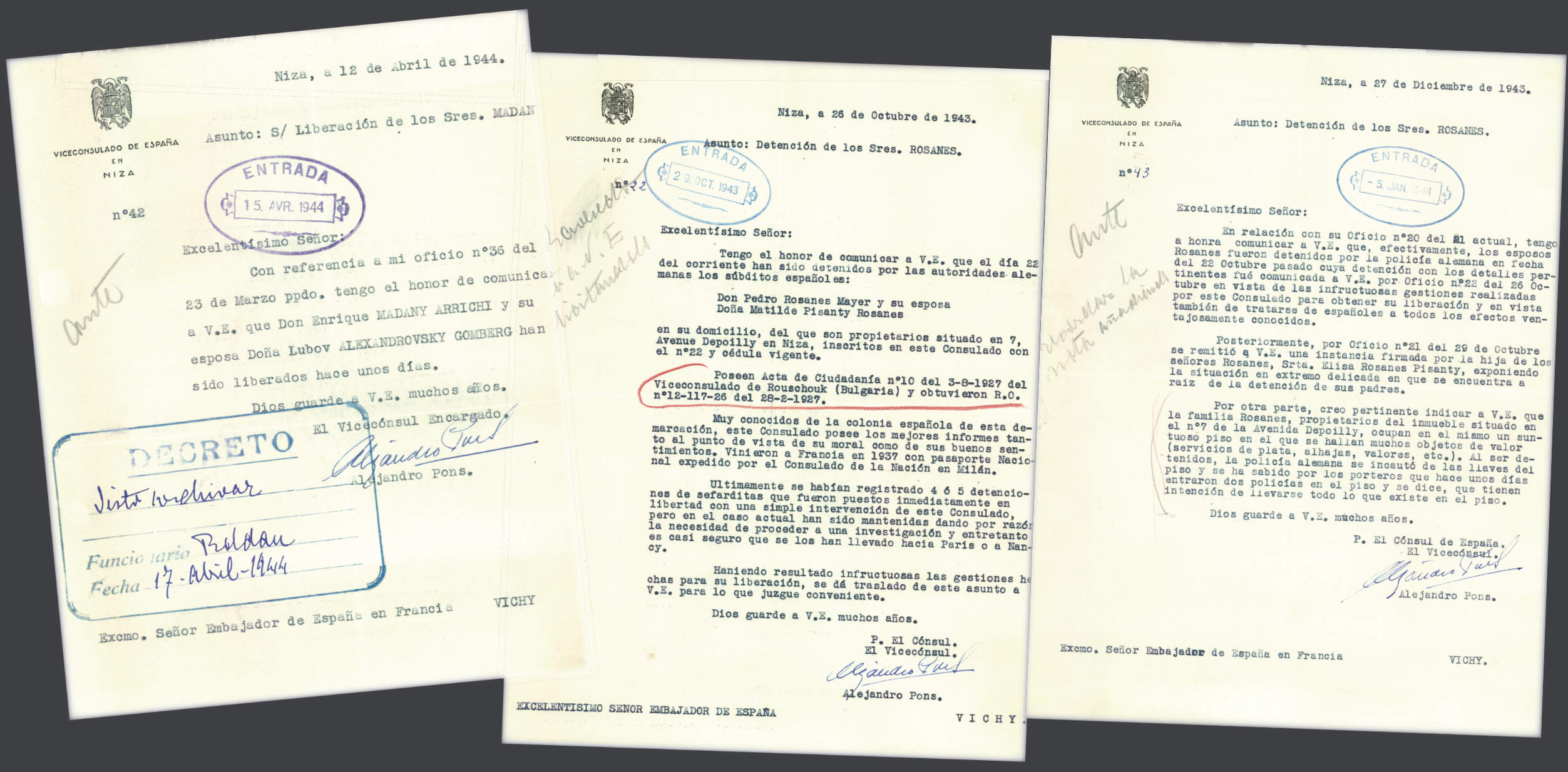

Pons's most praiseworthy humanitarian action was probably his determined struggle to liberate Jews arrested by the Gestapo; among them, in 1943, Max Feinstein Berlowitz and his wife (October) and Alberto Cohen Hassan (December). After arduous manoeuvres he achieved, in April 1944, the liberation of Enrique Madany and his wife, Lubov. While they were under arrest, through Pons's intercession, their 6-year-old daughter Lucía was taken in by former Spanish Republican MP María Lejárraga García, wife of the author Gregorio Martínez Sierra. When racial round-ups became the norm, the diplomat recommended that it was advisable for the local Spanish Jewish community to be repatriated to Spain, under the agreement with Berlin. Through a collective passport, in October 1943 he helped 15 adults, five children and a baby exit the country. Since inclusion on repatriation lists would facilitate the liberation of those deported to French concentration camps, the 39 registered in March 1944 include 12 detainees in Drancy, achieving freedom for seven of them. Afterwards, another two freed prisoners were included in the group of 22 sent out in a convoy in April 1944.

But if there is one case in which Pons made a truly tenacious effort, it was the liberation of Pedro Rosanes and his wife Elena Pisanty, arrested in Nice in October 1943 and taken to Drancy, from whence they would be deported to Auschwitz. Unaware of their tragic destination, Pons included them in the passport of the group to be repatriated in July1944. Meanwhile, he was personally involved in the guardianship of their daughter Elisa, a minor, whom he sheltered in his own home and later in the home of Sephardic Spaniards. He put her in touch with Ambassador Lequerica and the Bishop of Nice, and she begged them to intercede in the liberation of her parents. Moreover, the Vice-Consul processed different complaints about their imprisonment and the pillaging of their assets. In view of the constant plundering, he himself stuck the Consular Certificate of Spaniards' Assets on the door of their home.

Alejandro Pons died on 26 May 1944, near the Saint Laurent du Var station, killed by an Allied air attack when he was travelling by train to the Consulate in Nice from his residence in Cannes.

Loading

Loading