CHARGÉ D’AFFAIRES (BUDAPEST, 1942-1944)

ÁNGEL SANZ BRIZ

The miraculous multiplication of Sephardim

Ángel Sanz Briz (1910-1980) was the son of a wealthy merchant from Spain’s northeastern region of Aragon; his mother came from a military family. His brother Mariano would also become a diplomat.

In Egypt, his first post, he became acquainted with the local Sephardic community, which included many Spanish citizens. In 1941, when he became Chargé d’Affaires in Cairo, he issued — without authorization to do so — passports and safe conducts to certain former protectees

In May 1942, when he was 32, married and with a young daughter, he was posted to Hungary as a Secretary. In mid-June 1944, Minister Muguiro had to leave Budapest, and thus Sanz Briz became a young Chargé d’Affaires.

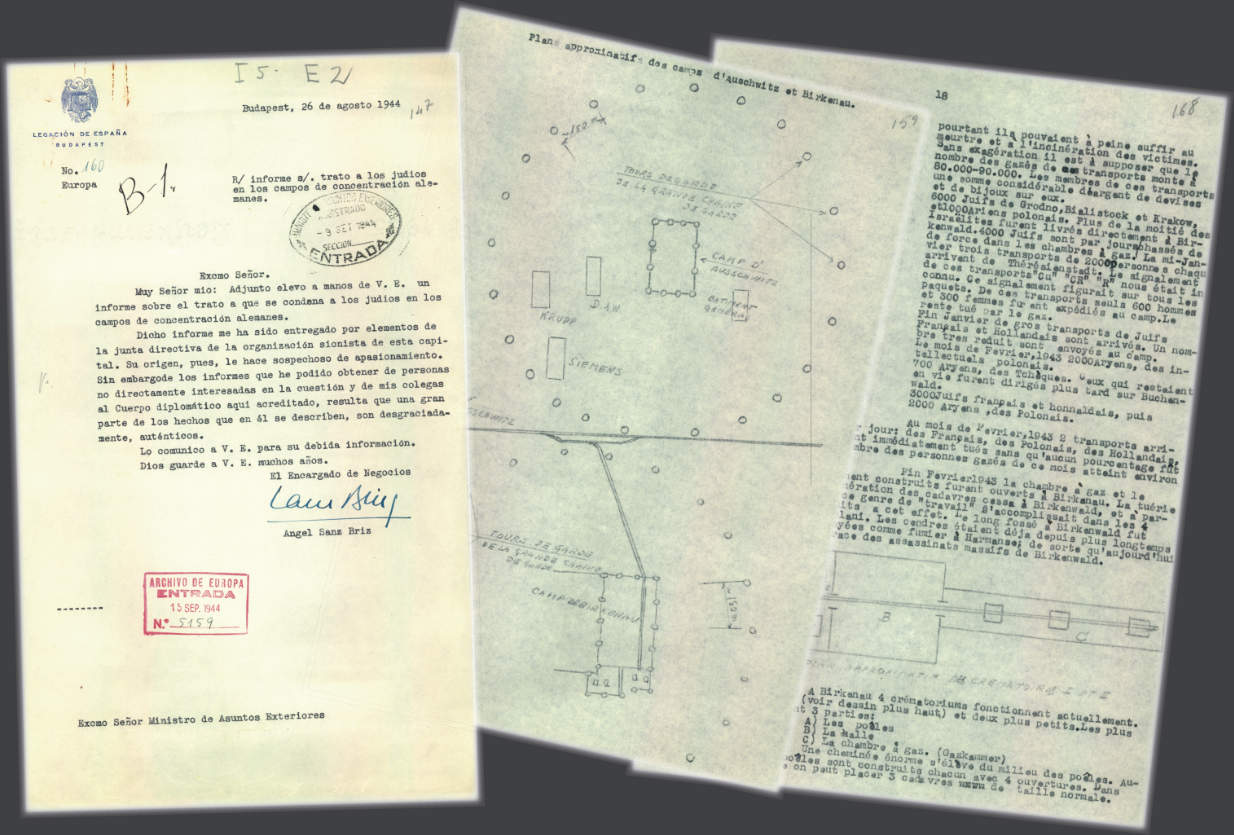

Alongside Muguiro, he had witnessed the escalation of racism in Hungary: first the enactment of anti-Semitic legislation, and then, beginning that summer, the deportation and extermination of half a million Jews. On 24 July he sent the Ministry a detailed 30-page report on Auschwitz, including the denunciation, by two fugitives from the camp, of mass murders in gas chambers.

In October 1944, Hungary’s Regent, Miklós Horthy, was overthrown and the Arrow Cross Party, led by the pro-Nazi Szálasi, took power. In view of the ensuing reign of terror, Sanz Briz took it upon himself, without prior authorization from Madrid, to rent houses for the Jews to whom he was giving protection. There were a total of eight houses protected by the Spanish flag in the International Ghetto. Moreover, there were also refugees staying at the Villa Széchenyi residence in Buda (25), at the Podmanski house (30) and in the Legation building itself (60). In addition, Spain was sheltering approximately 500 children in three Red Cross orphanages, whereas a hundred Jews were living in other “safe” places such as hospitals, maternity wards and retirement homes. Signs were put up on the façades of many of these buildings, stating that they were an “Annex to Spain’s Legation: Extraterritorial Building”.

Sanz Briz not only sheltered Jews in protected houses, but also, taking advantage of the prevailing confusion and anarchy in the city, provided them with a document called a letter of protection.

When the massive persecution of Jews began in Budapest, Sanz Briz decided that it was necessary to provide them with Spanish documents and — given that the war’s outcome was practically inevitable by then — obtained authorization from Madrid to issue them with documents of protection, on the basis of the 1924 Royal Decree. He designed a plan to issue passports: ordinary passports for Hungarian Sephardim and only provisional passports for Jews with family or relations in Spain. Afterwards, practically everybody who addressed the Legation received letters of protection, most of them with false information, but all of them official and on behalf of Spain.

Once he obtained Hungary’s agreement with the issuance of up to 300 safe conducts for Jews of Sephardic origin, Sanz Briz very cleverly turned those 300 units into 300 families which he in turn multiplied indefinitely by simply not issuing documents or passports with numbers higher than 300. They were all issued in countless series, each of them with different letters of the alphabet.

Instead of the 300 initial ones, he granted 45 ordinary passports, 235 provisional passports (many of these including several members of the same family, amounting to 352 persons), and 1898 letters of protection. However, the number of people he saved is even larger: it also includes the 500 under Spanish guardianship, several hundreds of provisional passports from Paraguay, and another group of 700. The great majority of Spanish protectees in Budapest survived the Nazi brutality and the Arrow Cross terror, and it is estimated that, in total, Sanz Briz was able to save approximately 5000 people.

The diplomat, resolved to risk not only his post and career but his very life, confronted Nazi officers in person to liberate several protected Jews from the well-known death marches towards Germany. This happened in mid-November 1944.

Sanz Briz would go on to have a brilliant career as an ambassador in Guatemala, Peru, the Netherlands, Belgium, China and the Holy See. He died in Rome at the age of 70, just before retiring.

On 18 October 1966, Yad Vashem recognized Angel Sanz Briz as Righteous among the Nations.

MINISTER (BUDAPEST 1938-1944)

MIGUEL ÁNGEL DE MUGUIRO Y MUGUIRO

Constant denunciation

Miguel Ángel de Muguiro y Muguiro (1880-1954) was posted to Budapest on 15 May 1938, at the age of 58 and after 31 years of diplomatic service.

Before being appointed Minister of the Legation in Hungary, he had been posted to Berlin (during the last years of the Weimar Republic, with a burgeoning Nazi party), to Rome (during Mussolini’s fascist dictatorship) and to Bucharest. There, between 1931 and 1932, he became deeply involved in Jewish issues: he processed the applications for Spanish nationality made by a large part of the local Sephardic community under the 1924 Royal Decree.

Muguiro was a strong proponent of the Monarchy; politically he was a member of Spanish Renovation — the party of José Calvo Sotelo and Ramiro de Maeztu — and he was a fervent Catholic, with two sisters who were nuns.

He collaborated closely with General Franco, and during the Spanish Civil War was appointed head of foreign policy of the body in charge of governing what was known as the National Zone, before Franco established his first council of ministers in January 1938.

In April 1938, a month before Muguiro took up his post in Hungary, the country adopted its first racial laws. The approximately 825,000 Jews in Hungary and in the annexed territories lived in relative peace until March 1944, the time of the German occupation and the designation of a pro- Nazi government which followed the orders of the Reich to exterminate the Jewish population.

From the outset, Spain’s new Minister in Budapest was very critical of the Hungarian government’s anti-Semitism. Between 1938 and 1944 he sent Madrid more than twenty communiqués solely to denounce racial decrees against Jews. As he explained in detail, these decrees involved, for example, prohibition to exercise any public activity (meaning the dismissal of all Jewish civil servants), obligation to wear badges and yellow stars, deposit of their silver, declaration of all their assets (often subject to looting, as were their businesses), forced participation in labour battalions, an prohibition to travel (making their evacuation impossible).

In March 1944 another decree was enacted, which, according to Muguiro, treated Jews “even more severely than German legislation on the same matter”. He reported this to the Spanish Ministry, and in subsequent reports he stated that “every day there are more and more detentions. Many of those arrested have been taken to German territory and interned in concentration camps there [...] many homes of Jews have been plundered by the Gestapo and their inhabitants abused by this notorious police force which continues to do whatever it wishes.”

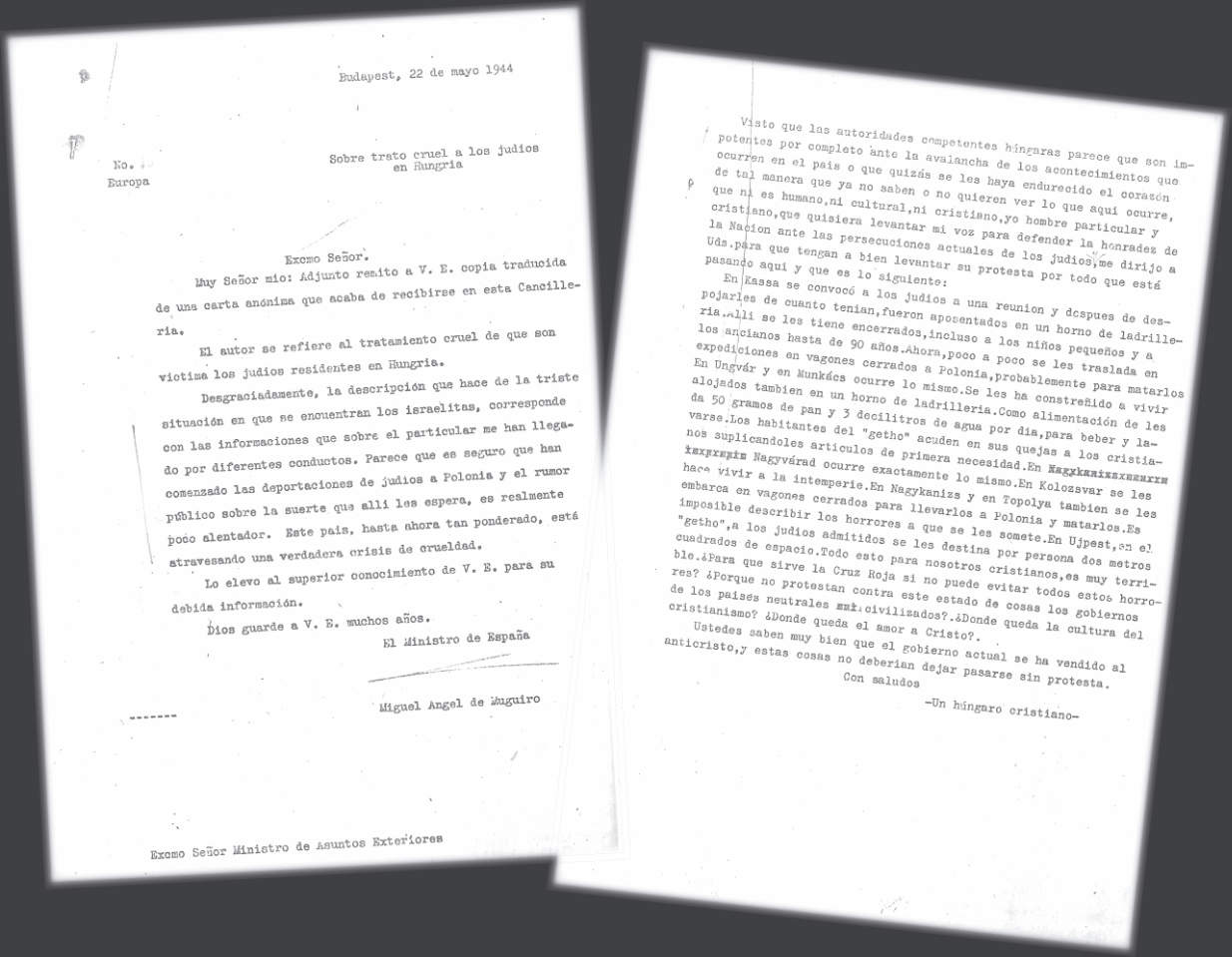

On 22 May 1944 he forwarded to Madrid a letter signed by “a Christian Hungarian”. The letter denounced the cruel treatment and plundering suffered by the Jews residing in Hungary, and how they were being taken in closed cattle wagons to Poland, probably to be killed. The diplomat stated that “unfortunately” this description corroborated other information he had received, and he concluded with these words: “This country, which to date had been so balanced, is currently undergoing a veritable crisis of cruelty.”

Following the Nazi invasion, and aware of how little time was left, he decided to immediately launch a rescue mission.

Thus, between late May and mid-June 1944, he issued Spanish visas to 500 Hungarian children aged 5-15, and to 70 adults accompanying them to Tangier. His aim was to save them from a death he believed certain. However, and despite the authorizations obtained by him and by the Red Cross for their exit from the country, in the end the Reich denied them transit. Protected from Nazi brutality by the Spanish Legation, and thanks to those documents, they remained safe in refugee camps, supported by the International Red Cross.

Miguel Ángel de Muguiro y Muguiro left Budapest on 18 June 1944, and left behind, as Chargé d’Affaires, Ángel Sanz Briz, a brilliant 34-year-old diplomat — no longer so young — who had served under him for two years, learning and witnessing the escalation of anti-Semitism in Hungary.

Muguiro retired as Consul General in Zurich in July 1950. He died four years later, without leaving any children.

Loading

Loading