MINISTER (BUCHAREST, 1940-1943)

JOSÉ ROJAS Y MORENO, COUNT OF CASA ROJAS

Simply Spaniards

José Rojas y Moreno, Count of Casa Rojas (1893-1973), arrived in Bucharest in early December 1940, at the age of 48, and after 25 years as a diplomat. He was fairly close to General Franco because, when the Spanish Civil War found him as Consul General in Tangier, he travelled to Tetouan to make his introductions. Franco received him several times in the early days of the uprising, and later in Burgos, as Head of State, appointed him Foreign Relations Secretary.

Romania was not the first place where Casa Rojas undertook to defend Jewish Spaniards. Before that, in 1938, as Head of the Europe Section, he ordered the Embassy in Rome — faced with the Italian government's decree to expel foreign Jews — to grant passports to all Spanish Jews because "since our legislation does not discriminate on the grounds of religion or race, there is only one kind of Spaniard".

In Bucharest, between 1940 and November 1943, thanks to his decisive intervention and to his friendship with members of the government — basically with the Prime Minister himself, Marshal Ion Antonescu, Conducӑtor de Rumania — he was able to prevent the application of anti-Semitic laws to the 110 Spanish Jews living there: albeit irregularly, their factories continued operating, their urban properties were respected, their automobiles and radios were not confiscated, and they were even exempted from a special tax imposed on Jews residing in Romania.

In April 1941, Casa Rojas was able to obtain the revocation of the expulsion of a group of 24 Jewish Spaniards (some of whom were actually Catholic) as well as the formal promise that in the future no Spaniard would be deported from Romania. He provided them with a certificate of inscription on the Legation's Register, stating that, as Spaniards, they were not subjected to the exceptional measures imposed on Jews.

At his own initiative, in February 1942, he advised naturalized Spaniards of Jewish origin not to register on the census of Romania's Central Jewish Office. Moreover, they were provided with placards from the Spanish Legation (signed by himself) for them to put on the doors of their houses, stating, in Spanish, Romanian and German, that such houses were under the Spanish Legation's protection.

In April 1941 he started to insistently remind the Conducӑtor Antonescu of the exchange of notes between Spain and Romania of 31 March 1934 for the application of the most-favoured-nation clause as regards the right to reside in the country and thus carry on with business and trade activities while preserving professional identity cards.

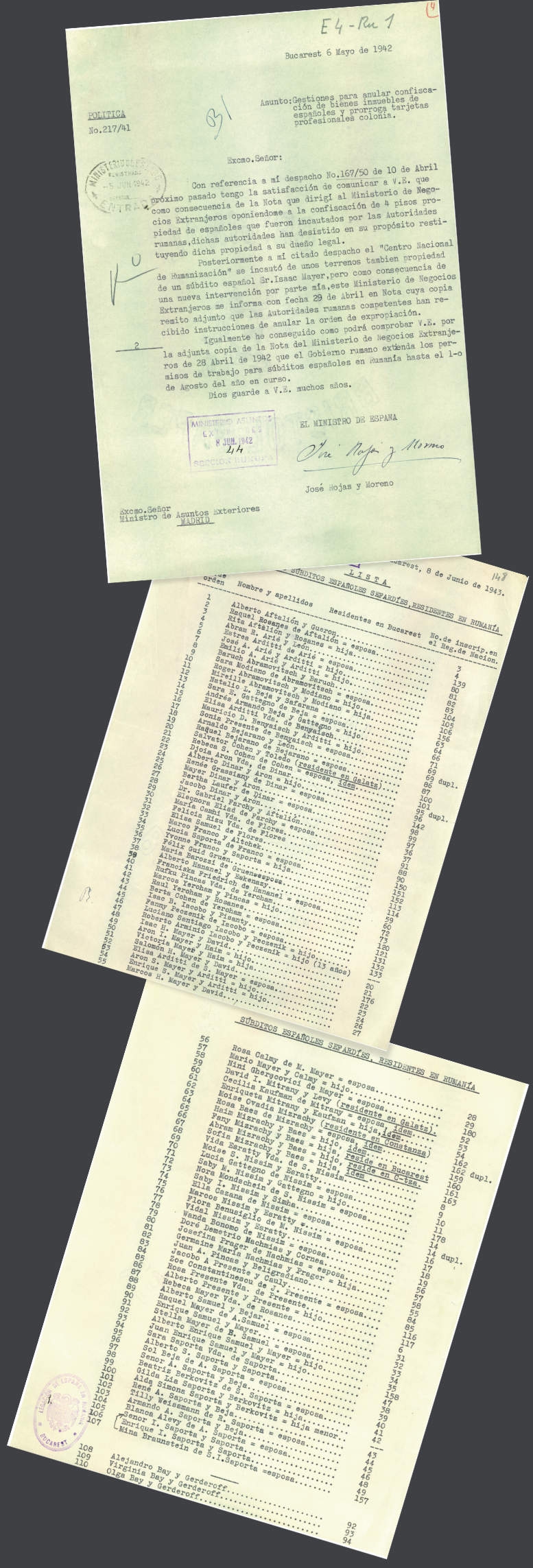

As a result of renewed opposition from Casa Rojas, in August 1942 Antonescu ordered the National Centre for Romanization to cancel the order issued for the confiscation of Spanish real estate and property: Spaniards were thus considered equal to Germans, Italians and Swiss.

For Casa Rojas, the Spanish Sephardim resident in Romania were simply fellow nationals. In his notes verbales to the Romanian government and at his meetings with Antonesco, he would talk about Spanish nationals without mentioning their Jewishness.

However, despite Casa Rojas's effective protection of the Sephardic colony, and faced with their possible future persecution in Romania, he attempted to get them repatriated "simply to cover their withdrawal and in the face of a desperate situation". On 26 September 1941 he demanded that Madrid approve the issuance of visas, without prior consultation or waiting for confirmation by the Ministry. He argued that, as a group, Jews had adhered to the National Cause during the Spanish Civil War, and that they had the moral and economic mic solvency to move to and settle in Spain. Finally, in May 1943, the Foreign Ministry granted him authorization "to facilitate travel if circumstances should so require", but it stressed that each case should be examined individually, which went against Casa Rojas's wishes. On 8 June he sent to Madrid and to the Spanish Embassy in Berlin a list of the 110 "Sephardic Spanish subjects residing in Romania" who met all the requirements considered essential. For them it was the beginning of the necessary evacuation permit when the time came.

Casa Rojas retired as an Ambassador in December 1962, after 47 years as a diplomat. Two years later, the government named him Permanent Member of the Council of State. He died in Madrid in 1973.

MINISTER (BUCHAREST, 1943-1945)

MANUEL GÓMEZ-BARZANALLANA Y GARCÍA, MARQUIS OF BARZANALLANA

A personal commitment

Manuel Gómez-Barzanallana y García (1876-1964) was nearly 68 years old when he was posted to Romania on 27 October 1943. He expected to reach retirement age at the Bucharest Legation, after more than 45 years as a diplomat.

His previous posting had been to London, as Consul General. Before that, he witnessed the beginning of World War II at the Spanish Embassy in Berlin, specifically the invasion of Poland by German troops.

He held the title of Marquis of Barzanallana, and had been a gentleman-in-waiting to King Alfonso XIII. There had been several Members of Parliament and Senators in his family during the Spanish Restoration (including his own father), and his grandfather had been Minister of Finance, President of the Council of State, and Speaker of the Senate.

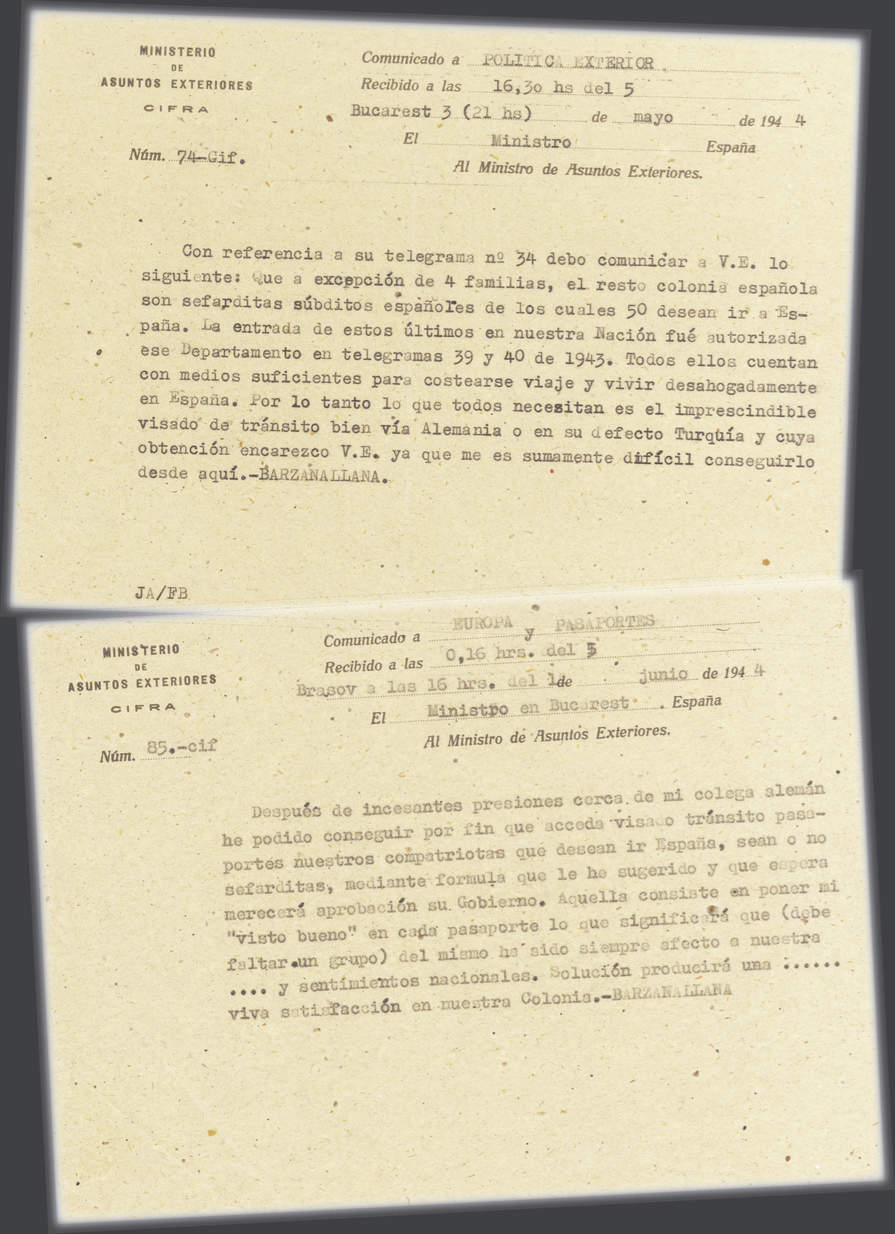

Faced with the distressing situation of the Spanish community in Bucharest due to the intense American bombing and the breakneck Russian advance, in mid-April 1944 the new Minister in Bucharest supported their wish for repatriation. Barzanallana decided to intervene to obtain the necessary transit visas, via Germany, or failing that, Turkey. Since he was not able to obtain them in Bucharest, he asked José Rojas y Moreno, Count of Casa Rojas — then Chief of Mission in Ankara — for the necessary documents for the 68 Spanish Jews who were still in Romania. Despite Barzanallana's efforts, the governments of Turkey and Great Britain ignored them and did not grant the necessary assistance to issue the documents.

On 1 May 1944, he was asked by Madrid if those who sought repatriation "are, strictly speaking, Spaniards or are Sephardim". Barzanallana answered that, except for four families, the others were Sephardic Spanish subjects. Of those, he said, 50 wanted to go to Spain — although there were actually 68. He added that they had already been authorized entry in 1940, as they were included on the list of 110 Jews sent to Madrid and Berlin by Casa Rojas. Days later Barzanallana expanded on his initial information, reporting that there was news that some six Jews were Catholic and another three or four intended to convert. He also sent two lists of "Sephardim with Spanish passports who live in Bucharest and wish to be repatriated". Both lists were drawn up by the Legation's Culture Attaché, María Victoria Jiménez: the first one was a list of Spanish Jews who were "Catholic or Catholicizable"; the second, of those who were "not Catholic and 1 don't know whether Catholicizable".

On 8 May Barzanallana received a secret telegram from Foreign Minister Gómez-Jordana, instructing him that only the 26 Spanish Jews who were Catholic or could possibly become Catholic were to be granted passports. Moreover, he was required to exercise great discretion vis-á-vis the other Spanish Jews "because it is not advisable for them to learn about this until they have departed". After his initial shock and indignation, Barzanallana decided to disobey the instructions received and ensure the evacuation of the entire group.

Even though Berlin denied the necessary transit visas through Germany, because they were for Jews, Barzanallana did not give up. Accordingly, he brought his case to the Nazis' Ambassador in Bucharest, reminding him of the precedent of evacuating Romanian Jews residing in France: the Reich had authorized their transit through Germany.

On 28 June 1944, Barzanallana's tireless efforts involving his German colleague, Baron Von Killlinger, made it possible for all his "fellow countrymen" wishing to go to Spain — Sephardic or not — to get the necessary seals of approval. He himself proposed how this could be carried out, a formula which was later approved by the German Legation in Bucharest and by Berlin. The German Embassy would stamp the transit visas for Spanish subjects resident in Romania wishing to travel to Spain "providing that their passports bore the 'approval' of Barzallana as an 'ideological guarantee of their respective holders' ".

Finally, in July 1944 the Spanish Foreign Ministry accepted that Barzanallana's "Spaniards"—whether Catholic Jews, "Catholicizable" Jews, simply Jews, or even those not initially authorized by Madrid — could come to their homeland, even though "eventually they must proceed on their journey and leave Spain". Given that the Spanish-French borders of Hendaya and Cerbere are closed, the diplomat asked Spain's Directorate-General for Security to allow them to enter and reside in Spain.

After Barzanallana retired from the diplomatic corps as an Ambassador, Franco named him a Permanent Member of the Council of State. He died in Madrid at the age of 88.

Loading

Loading